Ever since I’ve heard about Tuckerman Ravine and its renowned spring skiing I’ve wanted to plan a trip out to the White Mountains. Photos of its steep and exposed headwall look nothing like typical east coast glade and tree-cut skiing I was used to. A successful spring excursion and descent of the ravine seemed like a right of passage for those growing up in the area. Despite trying on several occasions, I was never able to get an outing out of the planning stage while I attended college relatively nearby in college. Unexpectedly an opportunity arose nearly 3 years after graduating when a spring reunion coincided with a great Friday opportunity to complete the Mt. Washington trek. Soon enough I flew out to Boston and made my way up to a friend’s cabin in nearby Franconia, NH.

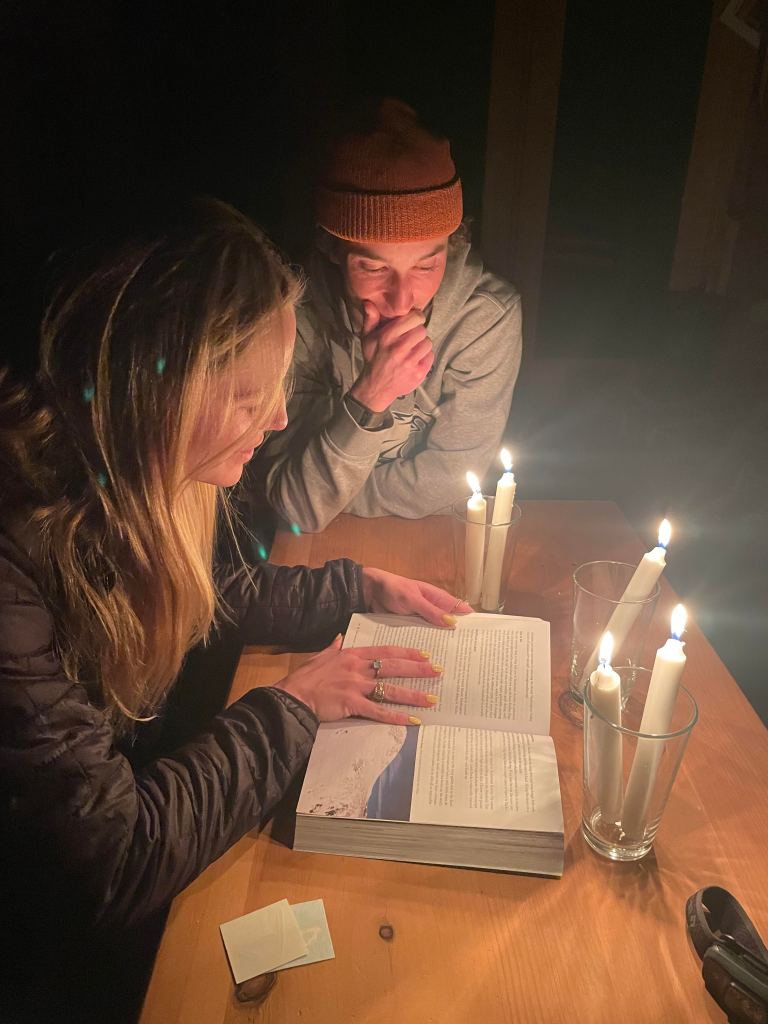

It was at the cabin that my friends and I started scoping out our lines in more detail with the help of “Best Backcountry Skiing in the Northeast: 50 Classic Ski and Snowboard Tours in New England and New York” by David Goodman. We figured the slope angles boasting 55+ deg headwall lines were quite sandbagged, but it put some fear into our minds while we still could enjoy the comfort of the cabin. This was the first time I would be putting myself into a true “no-fall zone” as most of the headwall required skiing above some massive cliff bands. At the time I knew my friends had skied the ravine once before, so I figured they could take some pressure out of the potentially terrifying descent. What I didn’t know at the time was that they both didn’t climb and ski the headwall itself, making our upcoming trek new terrain for us all.

Mt. Washington is most famous for its extreme Winter weather and highest peak of the American Northeast. Its not until the spring season that its two approach headwalls make for some fantastic ski descents. On April 26th, the three of us made our way from the Pinkham Notch trailhead to the base of Tuckerman’s Ravine. Starting off around 8 in the morning, we first hiked about a mile with skis on our back before transitioning into skins. Another mile or two went by before we made it to a cabin near the base of the ravine, which was packed with other skiers hungry for spring turns. Grace and Devin had both skied here before, which made me feel pretty good about spotting some crazy lines on the bowl visible from the base cabin. Although these looked pretty doable from below, I knew that this headwall was no joke. Looking at the guidebook the night before, most of the prominent descent options were above 50 degrees and very exposed – a fall would likely send you over the center cliff bands and be fatal. Knowing this should have been the first warning sign, none of us had arrest devices (an ice axe) and only myself had steel crampons. Grace had micro spikes and Devin had plain old ski boots, which are both wildly far from comfort when climbing 50+ degree snow.

Despite our lack of preparedness, we were super pumped up to begin our climb and knew we could turn around if things got hairy. For our first ascent we chose to climb straight up “The Chute”, which was a well defined and classic descent on the left side of the headwall. Starting from flat bowl basin, the slope rose immediately to about 30-40 degrees as we booted to a resting point underneath the rocky chute choke. We could see the steep main ascent and planned our route along the mostly defined boot pack on our right. The bootpack then traversed across the chute and onto a perch before we reached the main ascent exposure for another check in. At that point, Grace and Devin had barely made it across, evident of their gear failing to work at this slope angle. While we had recognized the rest of the slope was only steeper and likely not doable, I had agreed to move forward and dig a larger bootpack with my steel crampons into the snow ahead. At that point, I had all but committed to the full ascent due to the risk downclimbing and slightly better gear. However, Grace and Devin were in pretty poor shape. Deciding to turn back around, they slowly made it back to our first resting point with only a small slip in arrestable terrain. I could just barely see them on my ascent, but knew we had narrowly avoided a potential slip in exposed terrain.

Now climbing solo, I followed another climbing up the bootpack with increased apprehension. Falling at this point was not an option and I only had non-arrest ski poles and crampons to aid my ascent. Instinctively I knew the best way to continue was to stay calm and avoid panic. Loosing composure in that area would likely require a rescue and would only make my fear and risk worse. A healthy dose of adrenaline also helped, as I nearly sprinted my way up the steepest section of the headwall and into the rocky ridgeline ahead. The climber I had followed transitioned near me and gave me some reassurance that the ski descent would be possible, despite the incredibly intimidating rollover visible below. I gave myself probably 10 minutes at the top of the headwall to calm down, sip some water, and transition into my ski gear. The whole time I was on a relatively mellow slope prior to descending, but was on edge due to the strict no fall zone until I was about halfway down. Finally I began moving downhill on skis slowly, the whole time looking for tracks leading to the chute below. I was looking for a dogleg underneath a small cliff band, which traversed to the top of the line. Most of the way this was relatively mellow, but required one hefty turn at the steepest point and over the main headwall exposure. Inside I was terrified, but was able to keep my composure and move past the cliff band into the main portion of the chute. At this point I was incredibly relieved to make it past the no fall zone, but still had some crazy steep skiing ahead of me. I probably waited another five minutes or so to muster up courage before committing to the line. It was my first time experiencing sizable slough, small & loose avalanches that followed my turns across the chute. Despite this adding to the pressure, I made it down unscathed and felt incredible to have made it down the apron. At this point Grace and Devin had made it up to the top of “Left Gully”, a more mellow but still 40+ degree slope on the far left of the ravine. I sat by some rocks and watched their fast paced and mogul filled descent through the gully before meeting up with them at the crowded resting spot below.

Once we all made it down we celebrated the successful journey through the ravine. All of us had some great skiing despite the turnaround for Grace and Devin. I felt particularly glad to have kept my composure and executed some high consequence skiing. We drank some beers and made our way to the “Lobster Claw” for a last half lap and mellow bump skiing before our final transition on the way down. Overall the day was an absolute blast having skied with great conditions and weather. Stoke was high all around and we were able to witness some much better skiers than us rip lap after lap on the most technical ravine descents. Even our way down was great, the Sherburne trail was filled in for most of trip back to the trailhead (although we definitely met quite a few dirt batches on the way). When we finally made it down, we all felt completely spent and were excited to make our way back to Boston for the night.

Tuckerman Ravine can be relatively low risk if climbed and skied correctly, but we learned a crucial lesson about planning and preparation for this go around. Any ascent above 35-40 degrees really requires crampons, and any ascent above exposure really requires an arrest device. Moving forward we all have invested in gear that will make our future travel more safe and now know to be more mindful of researching beta prior to packing our final gear for a trip. Normal backcountry risks did not feel high during our approach and ski descent due to the good weather, snow conditions, and trail popularity. But in this case it was the terrain itself that carried high consequences. Keeping a level head and stopping when necessary was what kept us safe that day.